Package Management Infrastructure¶

This pages gives an overview of what components belong to Haiku’s package management infrastructure and how they work and interact.

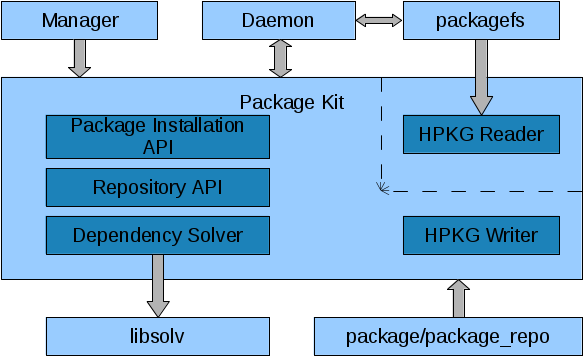

package and package_repo are command line tools for building package and package repository files. They are discussed in Building Packages.

packagefs is the file system that virtually extracts activated packages.

The package kit is an API for package management related programming.

The dependency solver is a part of the package kit. It solves dependencies between packages.

The package management daemon (short: package daemon) is a background process that is activated whenever the user adds packages to or removes them from one of their activation locations. It verifies that all dependencies are fulfilled (prompting the user, if necessary) and performs whatever package pre-activation/post-deactivation tasks are required. The daemon is also contacted by the package manager (after it has resolved dependencies and downloaded all required packages) to do the package de-/activation.

The package manager provides the user interface for software installation, update, and removal. There are actually two programs,

pkgman, a command line tool, and,HaikuDepot, a GUI application.

Software Installation Locations¶

In Haiku there are two main locations where software is installed. “/boot/system” and “/boot/home/config”. “/boot/system” is where system-wide software (i.e. software for all users), including the base system, is installed, while “/boot/home/config” is only for the user’s software. The discrimination between those two doesn’t make that much sense yet, but when Haiku supports multi-user it will (obviously each user will need their own home directory then, e.g. “/boot/home/<user>”).

At both main installation locations a packagefs instance is mounted. Each instance presents a virtually extracted union of the contents of all packages in the subdirectory “packages” of that location. E.g. if one would extract the contents of all package files in “/boot/system/packages” to an actual directory, that would match exactly what is presented by packagefs in “/boot/system”. With a few exceptions – packagefs provides several additional directories.

There are so-called shine-through directories which live on the underlying BFS volume. Normally a file system mounted at a directory would completely hide anything that is in that directory. These shine-through directories are handled specially, though; packagefs shows them just like they are on the BFS volume. One of those directories is “packages”. This is necessary since otherwise it wouldn’t be possible to add, remove, or update any packages. Further shine-through directories are “settings”, “cache”, “var”, and “non-packaged”. The latter is a place where software can be installed the “traditional”, i.e. unpackaged, way.

Software Installation¶

Manual Installation¶

At the lowest level software can be installed by simply dropping a respective package file in a “packages” subdirectory of one of “/boot/system” or “/boot/home/config”. The package daemon, a background process that sleeps most of the time, monitors the directory and, when happy with the newly added package, it asks packagefs to presents its contents on the fly in the directory structure. The package is said to be activated. Removing a package has the opposite effect.

Things are a bit more complicated due to the fact that packages usually have dependencies. E.g. when adding a package that has an unsatisfied dependency (e.g. needs a certain library that is not installed) it is not a good idea to activate the package nonetheless. The package contents (programs, libraries,…) might not work correctly, and, e.g. when shadowing other installed software, might even break things that worked before.

That’s why the package daemon doesn’t just activate any well-formed packages. Instead it examines the new situation and checks whether all dependencies are fulfilled and whether there are any conflicts. If they aren’t any problems, it tells packagefs to activate/deactivate the packages as requested. In case there are issues with the dependencies, according to how it has been configured via settings, the daemon prompts the user immediately, checks remote repositories for solutions to the problem and presents the user with the possible options, or it even performs all necessary actions without bothering the user, if possible. In the end, if the problems could be solved (e.g. by downloading additional packages), the respective packages will be de-/activated, or, otherwise, nothing will be changed.

To avoid always having to check all dependencies when booting, the package daemon writes the last consistent state of package activations to the file “packages/administrative/activated-packages”. When being mounted packagefs, reads that file and only activates the packages specified by it. If the file is missing or packages it refers to cannot be found or loaded, packagefs falls back to activating all packages in the “packages” directory. The package daemon, once started, checks the state.

Installation via Package Manager¶

While manual software installation is possible, the more comfortable way is to use the package manager. The package manager has a configurable list of remote software repositories. It knows what software is available in those repositories and what is installed locally. After the user has selected software packages to be installed/deinstalled, package dependencies are resolved, and packages are downloaded and moved to their installation location.

The package manager prepares a transaction directory, a subdirectory in the “packages/administrative” directory, which contains the new packages. It then contacts the package management daemon (via the package kit) to perform the package activation changes. The daemon moves the new packages to the “packages” directory, moves obsolete packages to an old state directory (also a subdirectory in the “packages/administrative” directory, with the current date and time encoded in its name) and asks packagefs to activate/deactivate the respective packages. The old state directories allow recovery of old states. That is particularly interesting for the system installation location. As as safe mode/recovery option, the boot loader offers the user to select an old installation state which can then be booted into, instead of the latest state.

Application Bundles¶

Haiku also supports a concept that is commonly referred to as application bundles. An application bundle is a fully self-contained package that doesn’t need to be installed anywhere. The implementation details have not yet been decided on. The basic idea is to either mount a dedicated packagefs with the content of such a package or have a special location where one of the three already mounted packagefs instances (likely the “/boot/home/config” one) shows that content. With a bit of Tracker (or even libbe) integration that will allow the mounted directory to be opened or the application to be started when such a package file has been double-clicked.

Installation Location Order and Consistency¶

Having two separate installation locations for software requires some

considerations regarding their consistency and interactions. There’s a

well-defined order of the installation locations: “/boot/home/config”,

“/boot/system”. This has already been the order in which on BeOS commands,

libraries, and add-ons where searched (according to the environmental variables

PATH, LIBRARY_PATH, and ADDON_PATH). That e.g. allows a user to

install a new/different version of a program in “/boot/home/config” and have it

override the version in “/boot/system”.

This order also needs to be the order in which package dependencies are directed. While it shall be possible to have a library in “/boot/home/config” override one in “/boot/system” and have programs installed in the latter location use the overriding library, packages in an installation location must not have dependencies that can only be resolved to packages installed in a location that is prior according to the order. E.g. a program installed in “/boot/system” must not depend on a library that is only installed in “/boot/home/config”. When going multi-user that would mean the program would work for one user, but not for another one who hasn’t installed the library. Consequently “/boot/system” is fully self-contained. All dependencies must be resolved within it. A safe-mode boot should be possible with only the “/boot/system” packagefs being mounted. As a consequence these constraints have to be respected when software is installed or uninstalled.

Another challenge that comes with having two installation locations is that some packages have compiled-in absolute paths to their own files (e.g. data files) or to their dependencies. The former could be solved by building two different versions of a package, but that wouldn’t work with the latter and would be tedious anyway. The solution are dynamically generated symbolic links in a fixed location, “/boot/system/package-links” (symlinked to “/packages”), that for each installed package and its dependencies refer to the respective installation location.

For each installed package a subdirectory named like the package (package name plus version) will be generated automatically. That subdirectory contains a symlink “.self” which refers to the installation location of the package itself as well as a symlink for each of its dependencies pointing to their installation locations. Furthermore there’s a symlink “.settings” which points to the installation location’s directory for global settings. E.g. for an OpenSSH package installed in “/boot/home/config” and OpenSSL installed in “/boot/system” the directory could look like this:

/boot/system/package-links/openssh-5.8p2-1/

.self -> ../../../home/config

.settings -> ../../../home/config/settings/global

haiku -> ../..

lib:libssl -> ../..

Installing a different, compatible version of OpenSSL in “/boot/home/config” would automatically change the respective dependency symlink. Once supporting multi-user fully, the symlinks targets would also depend on the user ID of the process that checks them, so software installed only for the user is handled correctly.

While it depends on the location the package has been installed in where the paths refer to, the absolute paths of the package links themselves remain stable. So they can be compiled in, when a package is built, and will work regardless of where the package is installed.

Another problem the package links can solve are incompatible versions of the same package being installed in different locations. E.g. when a program and another program it depends on are installed in “/boot/system”, installing an incompatible version of the latter in “/boot/home/config” will not break the former, since the dependency link will continue to point to the compatible version. With a bit of help from the runtime loader the same would work for libraries. In practice that’s less of a problem, though, since libraries usually have a naming scheme and matching shared object names that already prevent mismatches.

Software Repositories¶

A software repository is a collection of packages, usually accessible via the internet. Haiku’s package management solution allows to refer to any number of software repositories from which packages can be downloaded and installed. The structure of the respository is very simple. It’s just a set of files which can be downloaded via a common protocol (HTTP or FTP). One file is the repository index file in Haiku Package Repository Format. It lists all packages that are available in the repository together with their descriptions and dependency information. It is downloaded and cached, allowing user interfaces to show the information and the dependency solver to do the computation locally. The other files are the individual package files.

Standard Repositories¶

There are two standard repositories for Haiku:

the Haiku repository, which only contains the small set of packages that is built by Haiku’s build system (haiku.hpkg, haiku_devel.hpkg, etc.) and

the HaikuPorts repository, which contains the packages maintained by HaikuPorts.

For the different builds and releases there are different instances of those two repositories:

There are snapshot repository instances for any repository version that was ever available (to save space old versions may be removed/thinned out). Those repositories will never be updated. Their main purpose is to be able to retrospectively get a certain Haiku version for testing and comparisons.

For each official major release there will be an instance of the two repositories. For small updates the repositories will simply be updated. An official Haiku release is pre-configured with the corresponding repositories, so that the user can conveniently keep their Haiku up-to-date. The update to the next major release has to be requested explicitly.

Similar to the nightly images there are repository instances that are continuously updated to the latest head of development. Those are suitable mainly for testers and developers.

For each state of the HaikuPorts repository a Haiku development revision refers to a snapshot version of the repository is created. This allows to check out and build older Haiku revisions with their corresponding HaikuPorts packages.

The repositories are maintained via files in the Haiku git repository. For each architecture and each repository the Haiku git repository contains a file listing the packages for that repository. For the HaikuPorts repositories the packages are listed with the respective version. For the Haiku repositories the version is implied.

Whenever a developer wants to update or add a HaikuPorts package, the new

package file has to be uploaded to their git.haiku-os.org account and the

package list file for the repository has to be adjusted accordingly.

jam upload-packages <packages-list> can be used in order to upload the

package(s) or the packages could just be scp’ed into the ‘hpkg-upload’

folder in the developer home directory on git.haiku-os.org. When that is done,

the change can be pushed to git.haiku-os.org, where a push hook will analyze the

change, move the new package file(s) from the developer’s account to the

repository directory, and build a new repository snapshot. If a package file is

missing or broken, the push will be rejected with a message notifying the

developer about the problem.

The creation and update of repositories for official releases has to be triggered explicitly on the server. In either case the Haiku repository is built by the build service.

The Package Kit¶

The package kit provides an API for all package management related tasks, including:

Reading and writing HPKG and HPKR files.

Adding, removing, and querying software repositories.

Solving package dependencies.

Adding, removing, and updating packages.

Localization¶

Package files and repository index files contain text strings – e.g. the package short and long description – that are presented to the user. Therefore translations for these strings must be available. Since it is impractical to include the translations in the package and repository index files, they must be provided in separate files. How exactly has not been decided on yet.